What If We Took Message-Passing Seriously?

There’s a mass of data that holds a shape you can’t quite name. You poke it with a stick. It responds. You poke it differently. Different response. You start to get a feel for it, not understanding exactly, but something adjacent to understanding. A sense of what it wants to be.

That’s kind of where I am right now.

The Lens I Brought

First, a little bit about my background, because it explains why I built what I built.

I came up in Ruby. The language, sure, but also the culture. The one that thought maybe code could be poetry, or at least could aspire to poetry on its good days. The one that read _why’s poignant guide and understood that the foxes and the chunky bacon were a demonstration. Proof that programming could be a medium for creative expression, not just a tool for producing outputs.

There’s a difference between those two things. A piano is a tool for producing music. But it can also be a medium, a space where you discover what you have to say by saying it. _why treated Ruby like a medium. Most people treat most languages like a calculator.

I internalized the medium idea. Code as a place to think, not just a way to ship. And underneath the whimsy, there was a set of ideas. Many actually came from Smalltalk, from Alan Kay and team, from a vision of computing that never quite arrived.

Objects as little computers. Messages passed between them, interpreted by the receiver. Binding as late as possible. A whole system as a living thing you could reshape while it ran.

These ideas seeped into me through Ruby, through _why, and through years of thinking about what code could be. So now that this wave of AI has arrived and everyone is talking about “agents,” I find myself reaching for different words.

The Translation

When people talk about AI agents, they usually mean something like an LLM with tools, maybe some memory, pointed at a task. The interesting questions become: how do we make it reliable? How do we verify behavior? How do we add guardrails?

Good questions. Not my questions.

My questions are more like: what if we took Kay’s ideas seriously here?

What if an “agent” is more than just thing that does tasks, but a self-contained computing environment that can receive messages and interpret them however it wants? That’s objects as self-contained computers.

What if communication between agents isn’t function calls or structured APIs, but actual messages in natural language, interpreted by the receiver? Message passing.

What if we defer everything to runtime? Not just which function to call, but what the message even means? Let the receiver decide what the message means. Semantic late binding.

I started calling them “prompt objects” instead of “agents,” and the new name has reshaped how I think about them.

Sapir-Whorf for programmers: the words we use to think about a system constrain what you can imagine the system becoming. “Agent” primes you toward autonomy, tasks, guardrails, going rogue. “Prompt object” primes you toward thinking about composition, interfaces, inheritance, message protocols. Different words, different doors.

The Build

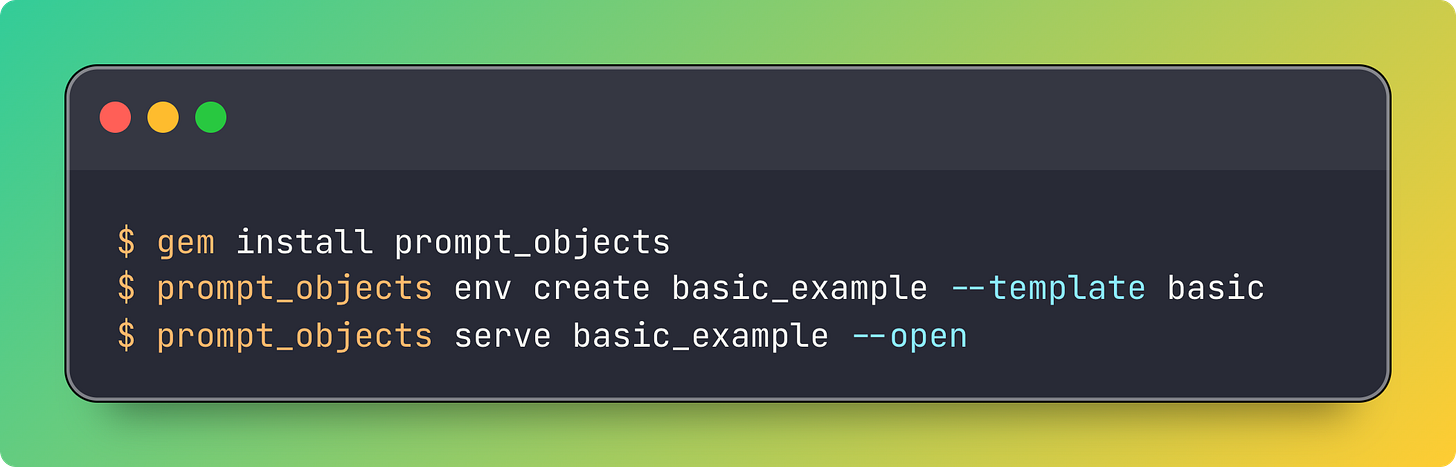

So I built a thing. I’m calling it prompt_objects, because I never did come up with a better name and at some point you just have to ship (even if Prompt Object Oriented Programming comes along with a tough acronym to shake).

It’s a Ruby gem (of course) for building systems of prompt objects that communicate via message passing. Smalltalk-inspired, where everything can be modified while the system runs (by you or even by other prompt objects).

A basic prompt object starts with only a few capabilities. It can receive messages, it can think, it can modify itself, and it can create other objects. That’s it.

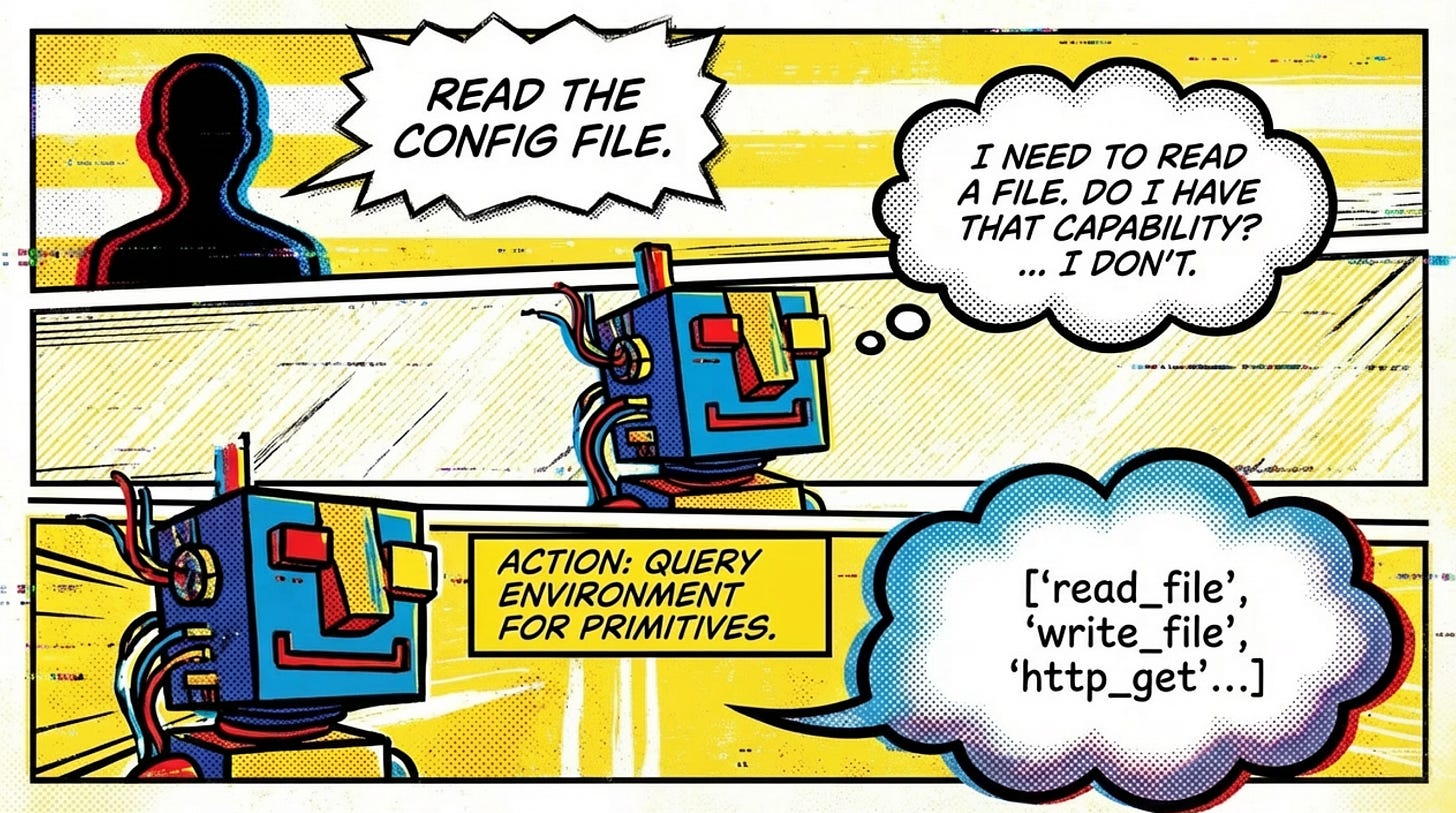

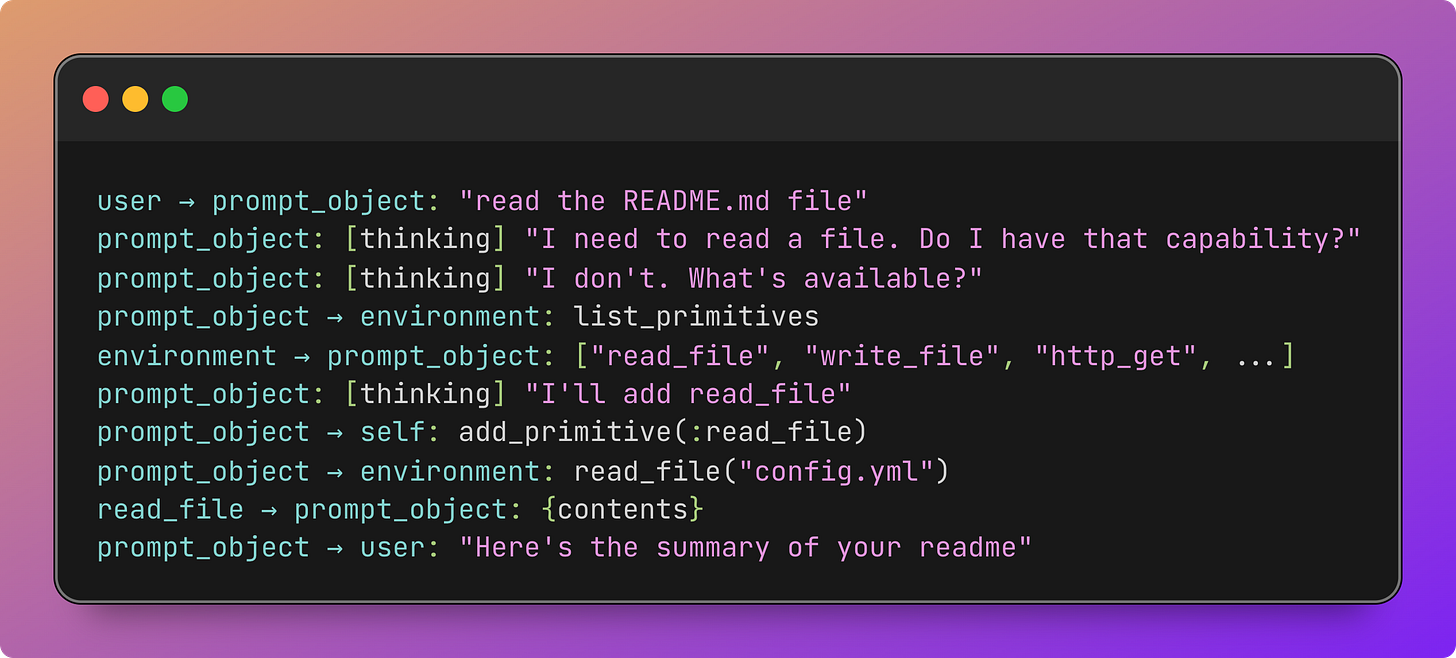

It receives a message to do something, read a file, say. It thinks about what it needs. Realizes it doesn’t have that capability. Queries its environment to discover what primitives are available in the equivalent of the standard library. Adds the capability to itself. Then uses it.

Self-modification as the default state.

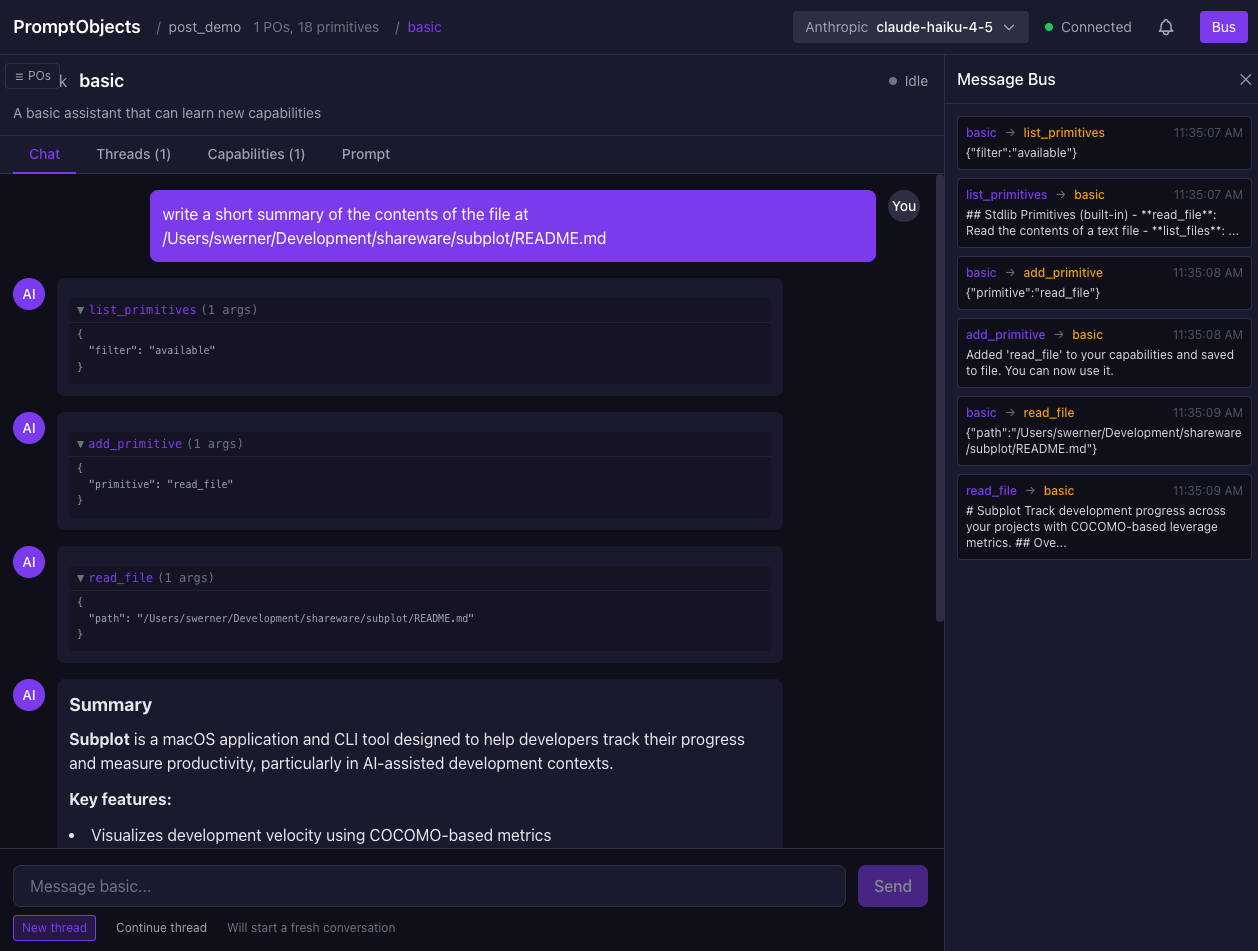

Here’s a screenshot of a very basic example:

And the way you can think about what’s going on here is essentially:

The object bootstrapping itself into competence.

What Emerges

When you take message-passing seriously, when the receiver actually interprets the message at runtime, in natural language, with all the ambiguity that implies, something shifts. The boundaries between objects become softer. The interfaces become negotiable. An object can ask another object what it’s capable of, and get an answer in prose, and figure out how to work together on the fly.

This is Kay’s “late binding” pushed to an extreme he probably didn’t imagine (I don’t think?). The binding is more than just late. It’s semantic. The meaning itself gets resolved at runtime.

And self-modification. When an object can add capabilities to itself based on what it encounters, the distinction between “the program” and “the execution” starts to dissolve. The system becomes a thing that grows.

You always hear people talk about how Smalltalk environments were places. You inhabited them. You could change them while they were running because they were alive in some sense.

LLMs might give us that back because they are able to interpret. They can take a message and decide what it means. They can describe their own capabilities in natural language. They can negotiate interfaces on the fly.

We accidentally built the runtime that (I think?) Smalltalk always wanted.

Or maybe I’m wrong. Maybe this is a dead end, a curiosity, a detour that leads nowhere. But so far it’s a fun detour. And over the past few years, I’ve learned to trust the fun.

Anyway

prompt_objects is available now. It’s on GitHub, it’s on RubyGems, it’s rough around the edges in the way that things are rough when someone’s still figuring out what they’re building.

I don’t have a grand theory. I just have a sense that there’s something interesting in this direction, in taking the old ideas seriously, in seeing what happens when you let objects be objects and messages be messages.

Kay said the computer revolution hasn’t happened yet. He said this in 1997. Not much has changed since then.

_why showed me that programming could be a place to discover things, not just a way to produce them. I’m still discovering.

This is what I found.

Love it! Yesterday morning I went for a long run and started thinking about agents, Alan Kay and LLMs. :) In particular I started thinking about a presentation of his where he talked about building computer systems that are more like biological systems rather than like machines: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NdSD07U5uBs&t=1486s

And I started thinking about a system of self correcting LLM agents. All very vague, very unclear ... and now I see that you already built it! :) I'm playing with it now, very interesting to explore!

Semiotics is calling you. Pick up.