Safe Is What We Call Things Later

Some Software Engineering Folklore

I was standing at the edge of the ocean last weekend watching the tide pools do their thing. This kid next to me, couldn't have been more than seven, was absolutely furious at the ocean.

"It keeps changing!" she yelled at the Atlantic, as if it might apologize. "Every time I figure out where everything lives, the water comes back and moves it all around!"

Her dad tried to explain about tides, about the moon, about gravitational pull. But she wasn't having it. She wanted the tide pool to pick a state and stick with it. Either be underwater or be exposed. Not this constant back and forth, back and forth.

"But then," her dad said, "nothing new would ever wash in."

"But then," she countered, "I could finally finish counting the hermit crabs."

And I stood there, salt air making my laptop bag feel slightly damp, thinking about how this kid had just described what it is like to be a software engineer. Except we don't have the moon to blame. We did this to ourselves.

The kid was fighting the tides, but we built ourselves a pendulum. Same back-and-forth, except we're both the clock and the clockmaker.

A Brief Philosophical Detour on the Two Kinds of Programmers

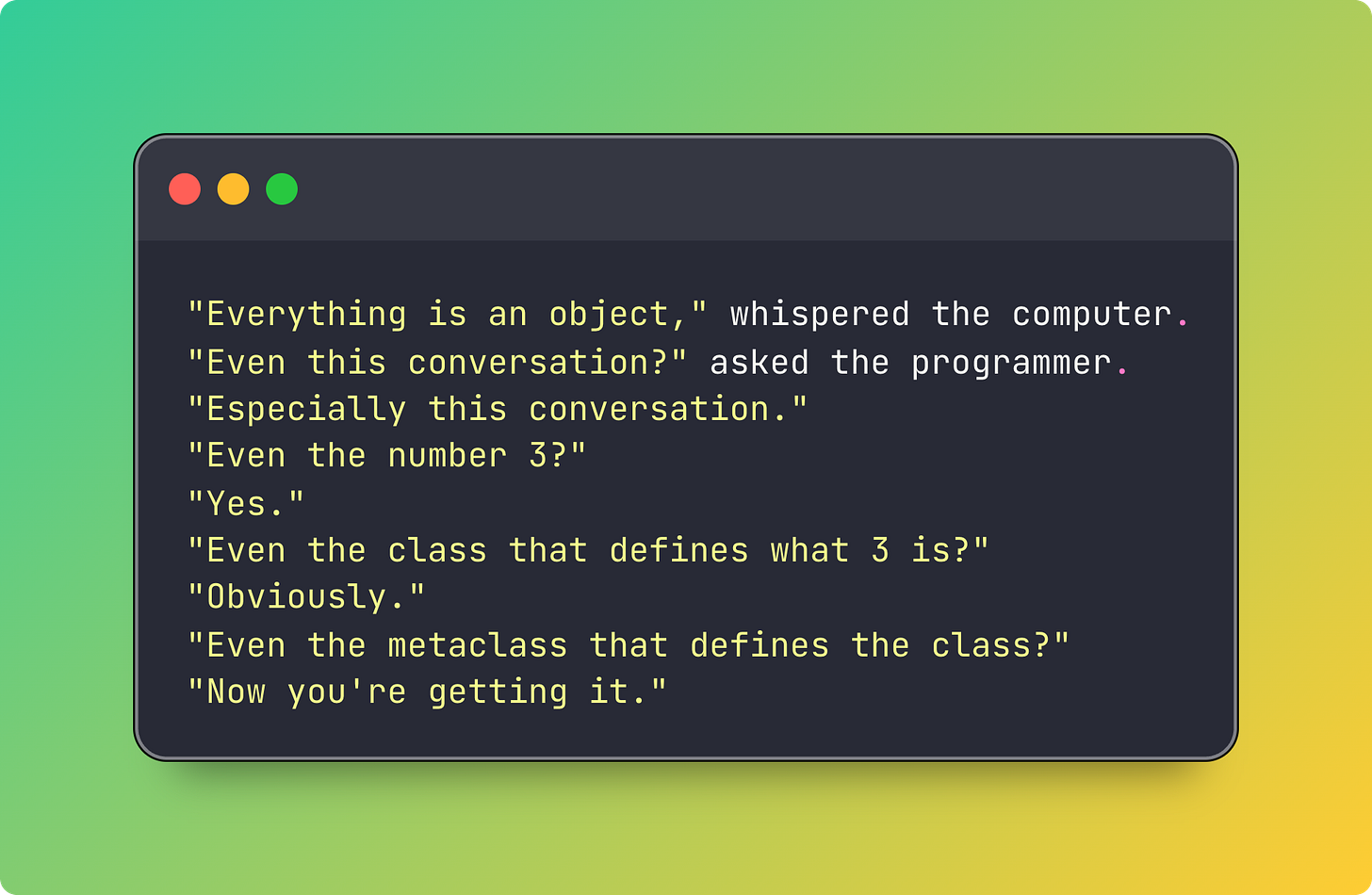

Avdi Grimm gave a talk called The Soul of Software about a decade ago and one particular thing in it has stuck with me: you can tell what type of programmer you were taught by based on which part of object-oriented programming they teach first.

Did your teacher start with inheritance? Class hierarchies, abstract base classes, the whole "a Dog is-a Mammal is-an Animal" taxonomy? Then you were taught by what we call a formalist. Someone from the Dijkstra school of thought, where programs are mathematical proofs that happen to execute. They showed you the blueprints before they showed you the building.

Or did they start with polymorphism? "Look, different things can respond to the same message in their own way!" Objects having conversations, duck typing, the magic of not caring what something is as long as it knows what you're asking? You had an informalist teacher. Someone from the Alan Kay school, where programs are living systems of communicating entities. They let you play with the clay before teaching you about kilns.

This isn’t just a teaching preference, it's two completely different universes of what programming is.

The industry has been switching between these universes, back and forth, like a pendulum, since the beginning of computing. And every time we switch, we act like we've discovered something new.

The formalists see programming as applied mathematics. Proofs you can execute. They sleep better knowing their types check at compile time.

The informalists (or the hermeneutic crowd, if we're being fancy) see programming as writing. As conversation. They sleep better knowing they can change anything at runtime if they need to.

(I was taught inheritance first. It took me years to recover.)

The Smalltalk Séance

Once upon a time, there were these folks at Xerox PARC who talked to their computers. Not like we do now, with our typing and our clicking, but really talked to them. They had this thing called Smalltalk, and it was less a programming language and more a conversation with a very patient friend who happened to be made of electricity.

They invented everything, basically. The mouse (someone told me it was originally supposed to be called the turtle. I don’t think that’s right… but it would have fit really nice with the ocean theme of this post… ). Windows you could move around like pieces of paper on a desk. Menus that dropped down like theater curtains.

But the real invention was the philosophy. Alan Kay wasn't trying to build better programs. He was trying to build better programmers. People who could think in systems, in conversations, in living breathing code that could change itself while running.

Meanwhile, in the Netherlands, Edsger Dijkstra was having nightmares about this exact thing.

The Dijkstra Doctrine

Dijkstra looked at programming and saw chaos. Not the good kind of chaos, where things emerge and evolve. The bad kind, where nothing works and nobody knows why.

"Programming," he said, probably while wearing a very serious expression, "is one of the most difficult branches of applied mathematics."

<That sound you just heard was Alan Kay spitting out his coffee.>

Dijkstra wanted proofs. He wanted to know, to prove, that a program would work before it ran. He wanted structured programming, where goto statements were considered harmful and every function had one entrance and one exit, like a very orderly party.

And you know what? He wasn't wrong.

When your code controls nuclear reactors, or airplanes, or insulin pumps, you don't want it to be having an exploratory conversation with itself. You want it to be a proof. A proof that happens to execute, but a proof nonetheless.

The Great Translation

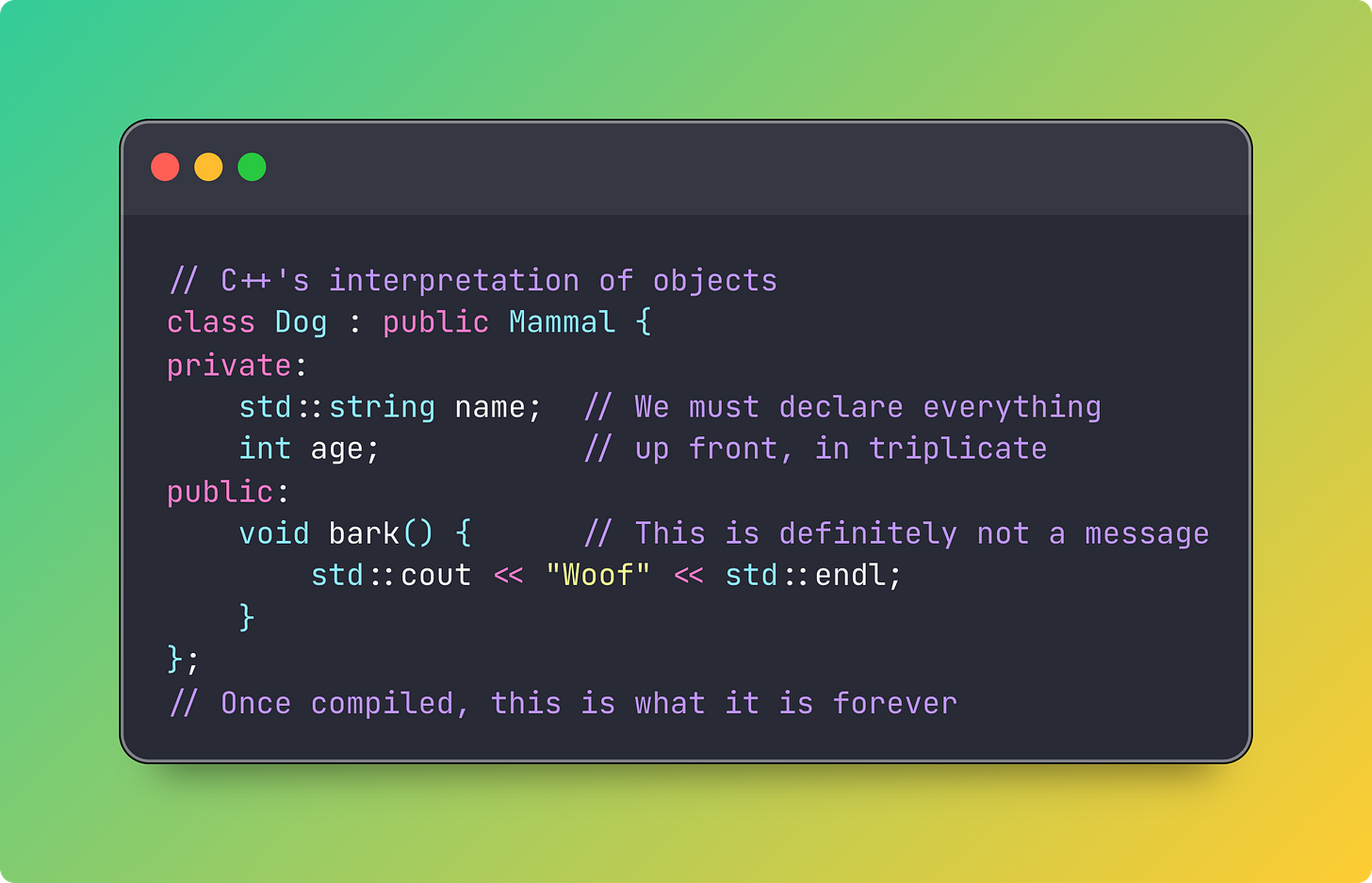

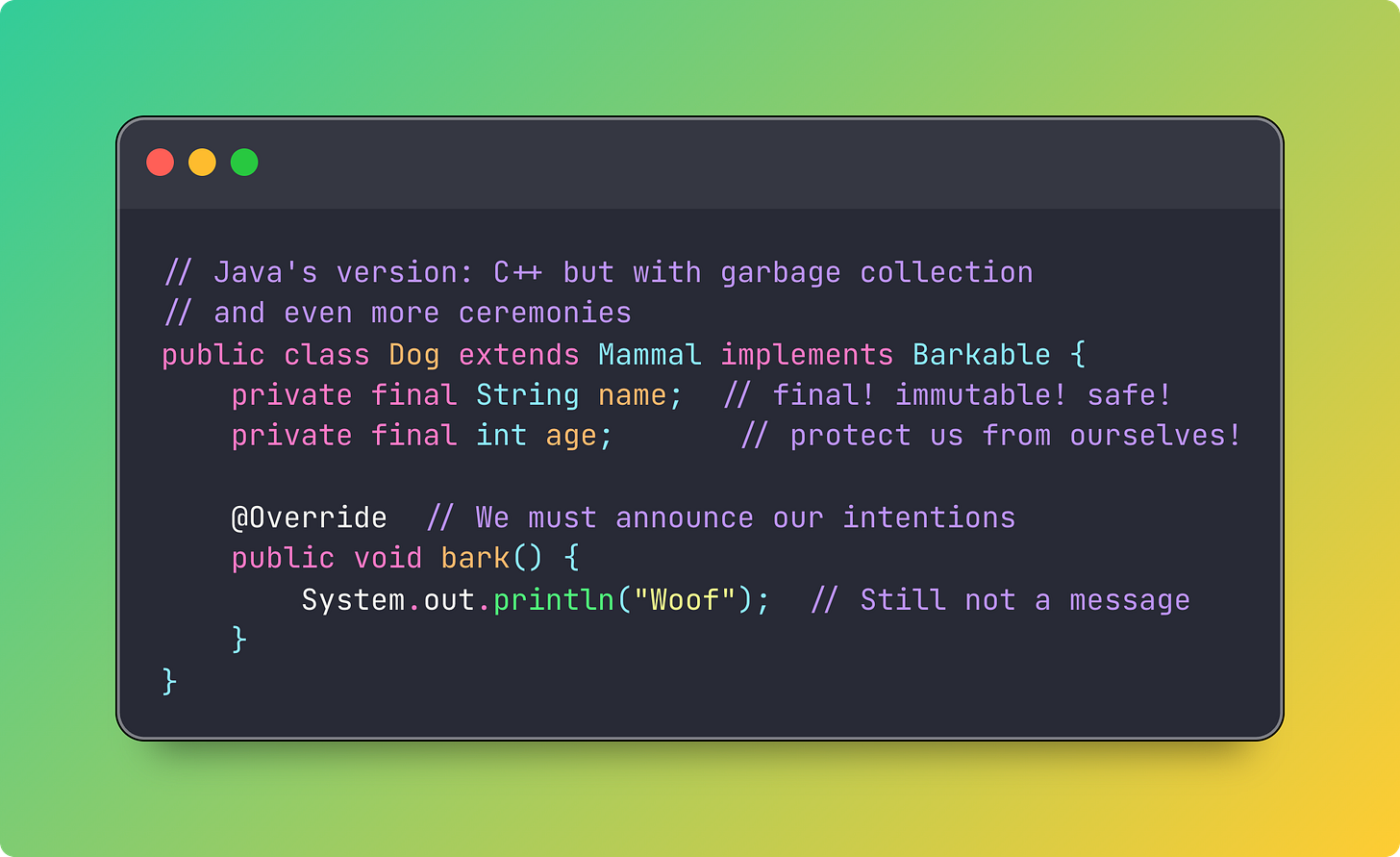

Now here's where it gets interesting. C++ and Java didn't just borrow from Smalltalk. They tried to translate Alan Kay's informal, living system into Dijkstra's formal, provable world.

Smalltalk said: "Objects send messages to each other."

C++ heard: "Objects have methods you can call."

Smalltalk said: "Everything happens at runtime."

Java heard: "Some things can happen at runtime, but let's check everything we can at compile time."

Smalltalk said: "The system is alive and you can change it while it runs."

C++ and Java heard: "...what? No. Absolutely not. Are you insane?"

They took the shapes of Smalltalk's ideas but filled them with concrete. Objects became structs with function pointers. Messages became method calls. The living system became a compiled binary.

It worked. It was reliable. You could build big systems with teams of people and the compiler would catch your mistakes. But something was lost. The conversation became a monologue. The living system became a corpse that somehow still moved.

The Web's Rebellion

Fast forward. It's the late 90s. Java is trying to eat the web. "Applets!" it shouts. "Enterprise beans!" it insists. Everything must be an object, everything must be typed, everything must be correct.

But then JavaScript happened.

And by "happened" I mean "was created in 10 days by someone who understood both Scheme and Self but had to make it look like Java for marketing reasons."

And from this beautiful combination came everything. Every web app you use. Every framework you love or hate. All built on a language that Dijkstra would have considered a war crime.

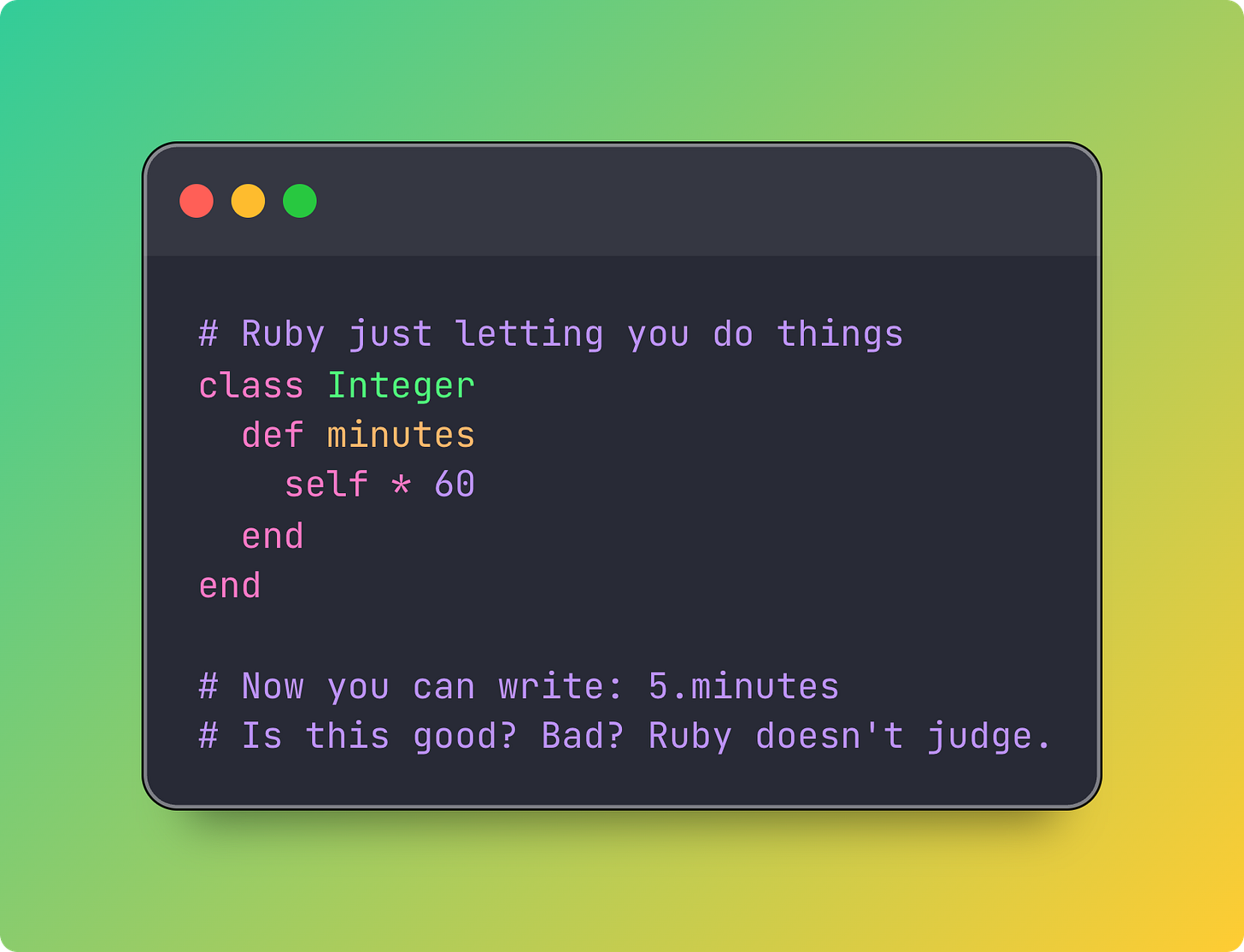

Then Ruby joined the party, taking Smalltalk's philosophy and saying "what if we made it even MORE flexible?"

Ruby on Rails said "what if making a web app was actually fun?" and suddenly everyone could build Twitter (the original one that was always falling over, but in a charming way, with an adorable whale).

The Alan Kay disciples were winning. Systems were conversations again. Code was alive, mutable, dangerous, and fun.

The Inevitable Tidying

But then (you knew there was a "but then"), the pendulum started its return journey.

The Rails apps that changed the world started creaking under their own weight. The JavaScript that let you prototype anything in an afternoon also let you create bugs that make you say “Wat?”.

Enter TypeScript, stage left, wearing business casual and a badge that says "I'm JavaScript but I was made by Microsoft."

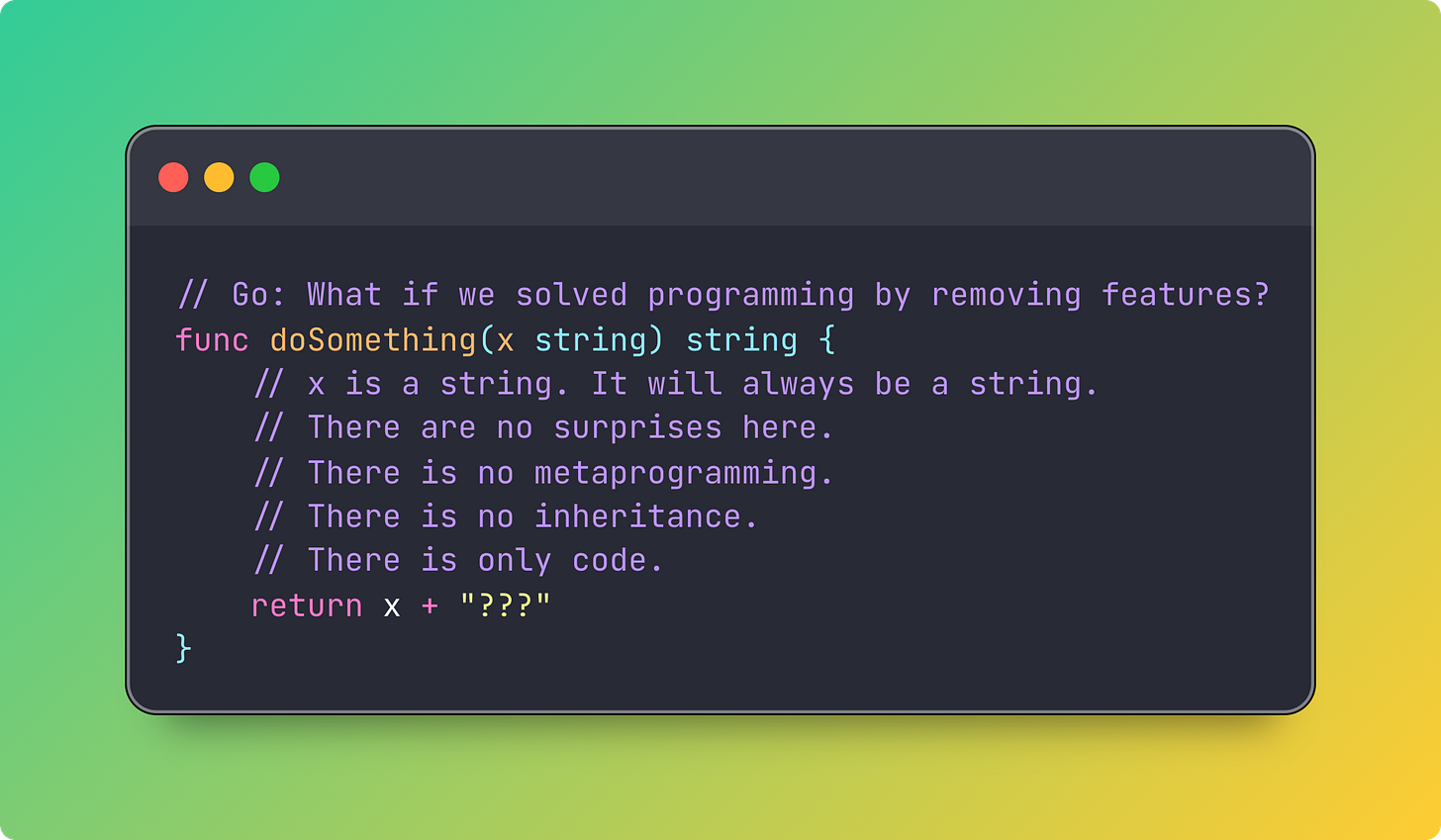

Enter Go, designed by people who looked at all the chaos and said "what if we just... didn't allow most of that?"

Enter Rust, which holds your hand so tightly while you program that you can't possibly hurt yourself (or anyone else).

(I'm only slightly exaggerating.)

Here We Go Again

But here we are again with AI, friends. We’re in the wildest informal moment yet.

People are doing things that would have gotten you laughed out of a code review five years ago. Vibe coding, where you don’t even worry about the code or the programming language and just let Claude figure out the details.

People are putting Claude Code directly on production servers. Not with guardrails or formal specifications. "Fix this bug," they say, and walk away. The code that results might work, might not. Who knows?

Last week, in The System Inside The System, I shared that I’ve kicked off some projects (vsm and airb) that lean all the way into this. Think about it, self-modifying Ruby agents that can rewrite their own capabilities while running. Systems that contain systems that contain systems. Code that writes code that writes code. It's either the future or a cautionary tale, and we won't know which until someone's production system becomes sentient.

We're back in Alan Kay territory, but turned up to eleven. These systems aren’t just alive and mutable, they’re writing themselves. Having conversations with themselves. Sometimes arguing with themselves in PR comments.

This is the informal approach at its most extreme. No proofs, just vibes. No types, just hope. No formal specifications, just "hey Claude, you know what would be cool?"

Someone asked me the other day, "Is it safe to let an AI modify its own code?"

And I said, "Define safe."

And they said, "You know, safe."

And I said, "No, I really don't."

Because safe is what we call things after we've formalized them. Before that, they're just experiments that haven't failed yet.

In a five years, maybe six, we'll start building formal systems around the AI use cases the informalists discovered. We'll develop new languages that have guard rails specifically designed for AI chaos. We'll create type systems that can type-check vibes. We'll invent testing frameworks for code that writes itself. Proof systems for agent behavior. Formal verification for self-modifying code. Strict sandboxes with fine-grained authority (hey Jonathan ;)). The Dijkstra disciples will arrive, and they'll make it safe.

The pendulum will swing back.

And then, inevitably, it will swing forward again.

Because that's what pendulums do.

The Pattern That Keeps Repeating

Look at any platform shift and you'll see it:

Desktop computing: Smalltalk wizards doing impossible things → C++/Java bureaucrats making it reliable (but losing the magic)

Web 1.0: Perl scripts held together with CGI and prayer → Java EE trying to enterprisify everything

Web 2.0: Ruby/JavaScript cowboys building and shipping in the same breath → TypeScript/Go/Rust bringing adult supervision

And now, AI: "What if we let the machine write itself?" → [PENDING: Whatever we'll invent in 3-5 years to make this safe]

The informalists, they explore the possible. They say "what if?" and "why not?" and occasionally "oops." They build things that shouldn't work but do.

The formalists, they make the possible reliable. They say "prove it" and "define it" and "what about edge cases?"

We need both. Not at the same time (that would be chaos (the bad kind)). But in sequence, like breathing. In like exploration, out like formalization. In like play, out like proof.

The Real Secret

You want to know the real secret? The thing that nobody admits in blog posts (except, I guess, this one)?

We need both types of people. We need the ones who see a cliff and think "I wonder what's at the bottom?" And we need the ones who see the same cliff and think "we should probably build a bridge."

The informalists and the formalists, they're not having different conversations. They're having the same conversation at different times.

The informalists are asking: "What's possible?"

The formalists are asking: "What's sustainable?"

Both questions matter. Neither is more important than the other.

(Okay, sometimes one is more important than the other, but only temporarily, and sometimes it depends on whether your daily deals site keeps crashing on black friday.)

And somewhere, in that eternal swing, we occasionally build something that actually matters. Something that changes how people think or work or live. Something that takes us one step closer to the computer revolution that hadn’t happened yet in 1997 but still hasn’t happened in 2025.

The girl never did finish counting her hermit crabs. The tide came in while she was still yelling at it. But I saw her there the next day, at low tide, starting her count all over again. This time she wasn’t angry. She was excited.

“They’re all in different places!” she told me. “New ones washed in!”

And that, my friends, is exactly my point.

Yes, I know you might think my self-modifying Ruby agent framework is part of the problem. But it also might be the solution. Depends which side of the pendulum we're on when you read this.

This is just a fantastic historical summary!

It reminds me of Simon Wardleys component evolution cycles in which all products evolve over time from Genesis to Custom Built to Product to Commodity & the tools required for each stage differ - https://medium.com/wardleymaps/finding-a-path-cdb1249078c0

Really fun piece, thanks for writing!