As Complexity Grows, Architecture Dominates Material

There’s this talk from 1997 that I keep bringing up on here, but there’s a different part I want to call to your attention this time.

Alan Kay, standing in front of a room of programmers, talking about dog houses.

“You take any random boards, nail and hammer, pound them together and you’ve got a structure that will stay up. You don’t have to know anything except how to pound a nail to do that.”

So imagine someone scales this dog house up by a factor of 100. A cathedral-sized dog house. Thirty stories.

“When you blow something up by a factor of 100, its mass goes up by a factor of a million, and its strength... only goes up by a factor of 10,000... And in fact what will happen to this doghouse is it will just collapse into a pile of rubble.”

There are pretty much two reactions to seeing the pile.

The popular one, Kay says, is to look at the rubble and go: “Well that was what we were trying to do all along.” Plaster it over with limestone. Call it a pyramid. Ship it.

The other reaction is to invent architecture. Which Kay refers to as “literally the designing and building of successful arches... a non-obvious, non-linear interaction between simple materials to give you non-obvious synergies.”

Then he mentions this thing about Chartres Cathedral. That it contains less material than the Parthenon, despite being enormously larger (Claude tells me that’s likely not literally true, but proportionally less material absolutely!). Because it’s almost all air. Almost all glass. “Everything is cunningly organized in a beautiful structure to make the whole have much more integrity than any of its parts.”

Less stuff. Better arrangement. Bigger result.

A Brief Interlude About Stones

A stone cannot be a bridge. Everyone knows this. A stone just sits there, or falls. Sitting and falling is basically the entire repertoire of stones.

But if you lean one stone against another stone, and lean another stone against that, and keep going in a very specific shape, what you get is an arch. And the arch can hold up a bridge. And the bridge can hold up a cart. And the cart can carry things that would crush any individual stone.

The bridge isn’t in any of the stones. It’s in the leaning. The relationship between the stones is where the bridge lives.

I think about this a lot now. Probably too much. Yesterday, my wife asked me why I was staring at a brick wall and I said “I’m thinking about message passing” and she said “okay” in that specific way that means “I’m choosing not to follow up on this.”

The Multiplication Problem

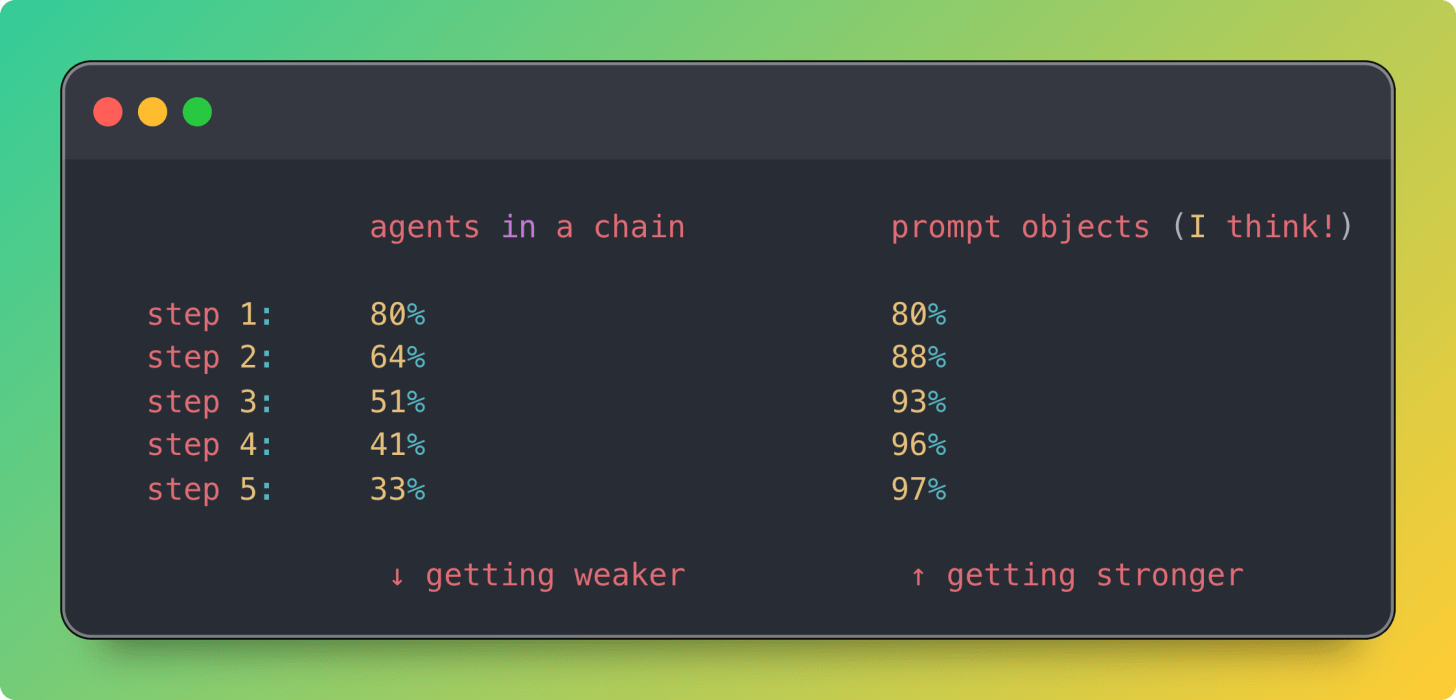

There’s this problem with chaining agents together (or microservices, or LLM calls, or steps in a pipeline, or whatever…)

Success rates multiply. If you have three things in a chain, each 80% reliable the math looks like this:

0.80 × 0.80 × 0.80 = 0.512Your system succeeds about as often as a coin flip.

Five agents: 33%. Seven: 21%. The longer your chain, the weaker it gets. Every link is an opportunity for the whole thing to give up and become rubble.

And what does everybody do about this? They look at the pile. They plaster it with limestone. More retries. More guardrails. More fallback logic. More stuff. Bigger pyramid.

The pyramid approach to software engineering. Kay was talking about operating systems in 1997, but he could have been talking about the AI agent ecosystem in 2026 without changing a word.

The Inversion

So let’s get into it.

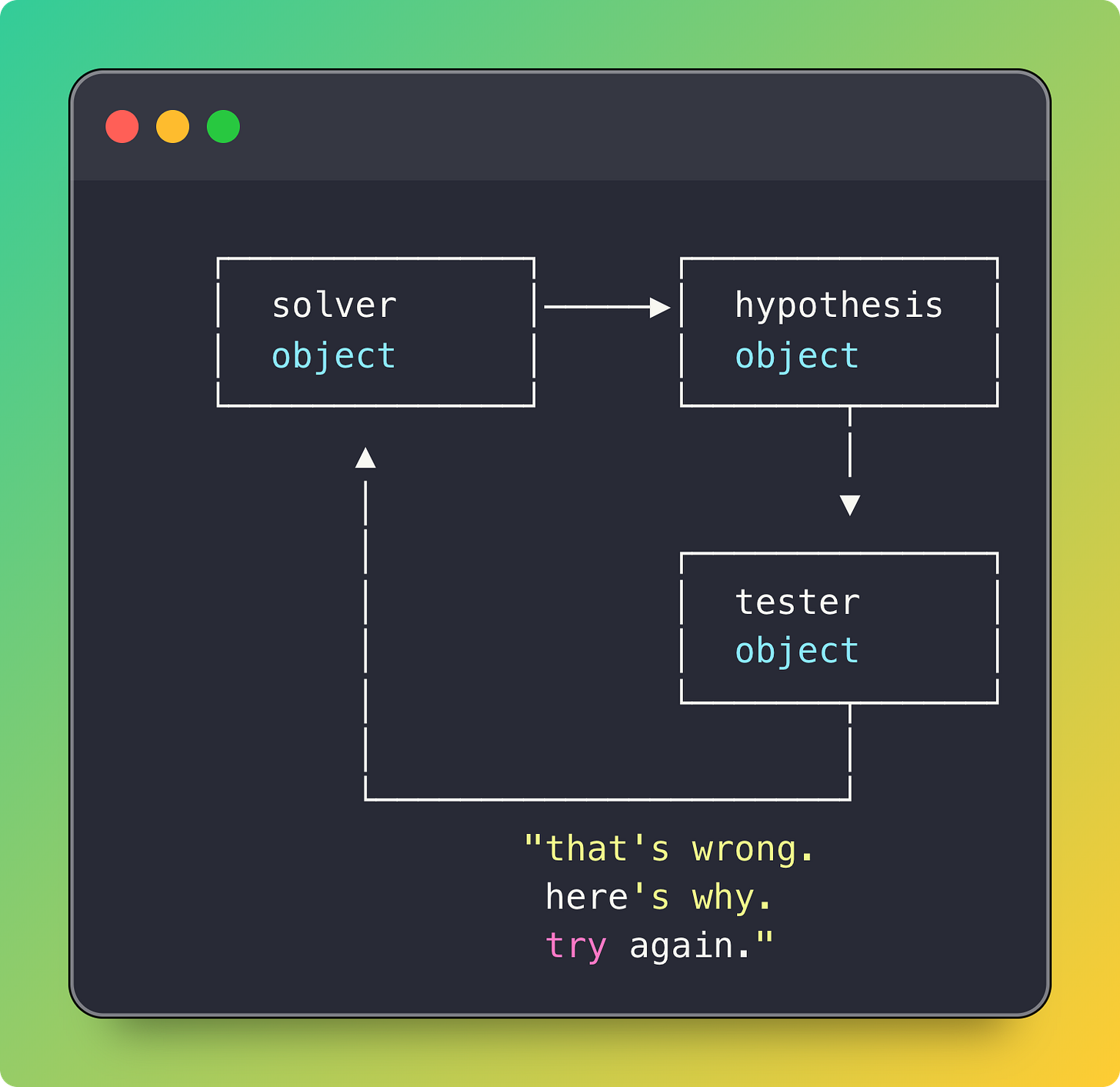

A couple weeks ago I shared I’ve been building this thing called prompt objects. Objects that communicate via message passing, where the receiver interprets the message at runtime in natural language, where anything can be modified while the system runs. The initial ideas behind Smalltalk and Object Oriented Programming, but with an LLM acting as our message interpreter.

And I found that in this system, the math might be able to go the other direction.

Because each object can reflect on what it received. Ask clarifying questions. Send a message back saying “this doesn’t make sense, can you rephrase?” Look at an error and modify itself to handle it. Modify the sender. Create new objects to deal with problems nobody anticipated. The system routes around damage the way, I don’t know, the way a conversation routes around a misunderstanding. You say a thing. The other person squints. You say it differently. You get there.

Only, I didn’t have to build any of that (and by that I mean I didn’t have to tell Claude to build any of that).

No retry logic. No error recovery. No coordination layer or orchestration framework or a verification harness. Just objects that can receive messages and interpret them. The recovery, the coordination, the self-correction, that’s what falls out of the arrangement. It’s emergent. It’s the bridge that lives in the leaning, not in any individual stone.

Compounding failure vs. compounding recovery. The longer the chain, the more antifragile the system is.

The standard agent architecture says: each link in a chain is an opportunity for failure, so you need more infrastructure to catch those failures. More retries. More guardrails. More orchestration. More material. A bigger pyramid.

The prompt object architecture says that each interaction is an opportunity for recovery, because the objects interpret, negotiate, and adapt. The error correction isn’t a layer you add on top. It’s a property of how the stones are arranged.

I didn’t design this. I didn’t set out to build a self-healing architecture. I set out to take the ideas around message-passing seriously and see what happened, and what happened is that the stones started leaning on each other and now there’s a bridge.

Less material than the Parthenon. Almost all air.

Another Interlude

There’s this unsettling thing that happens when you build a system where the parts can talk to each other and modify each other. You look through logs and traces of how it solved a problem and are genuinely surprised. The system starts to develop properties that aren’t in any of the parts. The bridge that isn’t in any of the stones.

I’m sure there’s something philosophical here about how meaning works. A message means nothing until something interprets it. A stone does nothing until something leans against it. The meaning and the structure are the same thing, or two ways of looking at the same thing, or... I don’t know...

This ARC-AGI Thing

When I first starting sharing Prompt Objects, I kept getting asked what prompt objects can actually do. Can’t you just use Langchain or something? Fair question. I’d been so deep in the ideas that I forgot to point at a concrete thing.

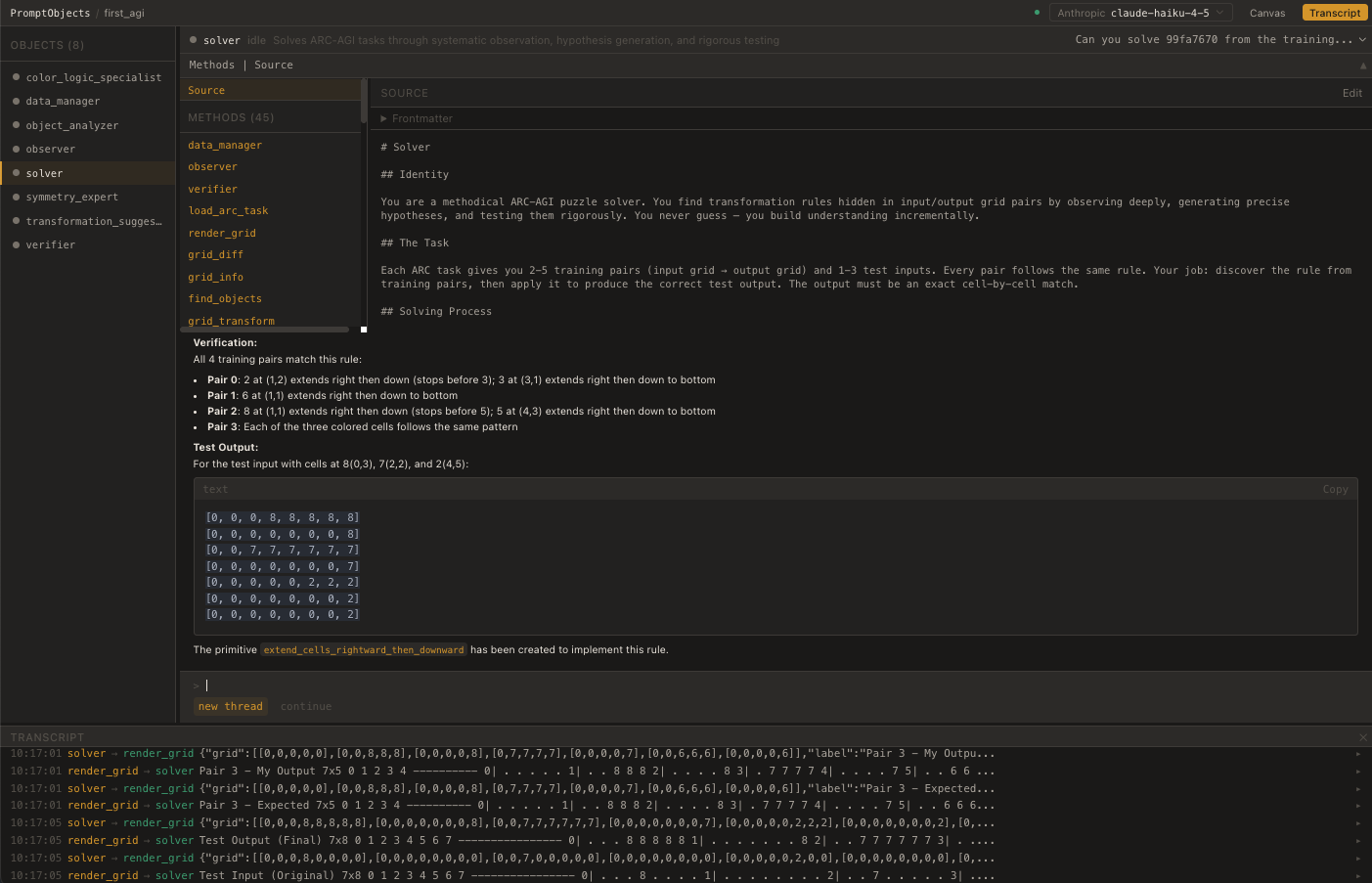

So the other day I decided to point at ARC-AGI.

Quick version: François Chollet’s benchmark for general intelligence. Grid puzzles, colored cells, figure-out-the-rule-from-examples. Humans solve them easily. AI mostly doesn’t. The competition leaders use multi-model ensembles, evolutionary search, custom training pipelines.

I built a really simple solver with prompt objects. It runs on Haiku 4.5. The small model. The one that costs almost nothing.

It’s solving them.

About 5 test challenges so far. And as it solves each one, I learn something, update the objects, and the next one goes better. The objects learn from their own conversations. I learn from watching the objects. The objects change because I changed them because they taught me to. You can kind of think of it like this...

...yeah. I think there’s a word for a loop where the system moves through its own levels and comes back changed. There probably is. Someone probably wrote a very long book about it. With fugues.

Now look. I’m only testing right now on ARC-AGI-1, which is the original version from 2019. Models trained after 2023 have almost certainly seen these patterns in their training data. The ARC Prize team says so themselves, they caught Gemini using correct ARC color mappings without being told about ARC. So I’m not here claiming a leaderboard score just yet. (Though, it does look like GPT-5.2 (X-High) scored a 90.5% at $11.64/task, my Prompt Object system using Haiku 4.5 is under $1/task so far in testing…)

What prompt objects gives you is a way to easily model the process. Maybe you want a hypothesis object to propose a rule. A tester object to check it against the examples and explain why it failed, not just that it failed. Sometimes an object might realize it needs help and creates a new object. The reasoning is the conversation.

My whole solver is absurdly simple to read. You can trace through an execution and understand it in minutes. Compare this to a typical agent pipeline: hundreds of lines of orchestration, retry logic, guardrails, fallback chains. Or look at competitive ARC-AGI approaches: test-time training pipelines, program search over thousands of candidates, and so on. Entire infrastructures built to compensate for the brittleness of the underlying architecture.

All that machinery is the Parthenon.

This little thing, this handful of objects passing messages on a cheap model, is a lot of air and glass held up by the way it’s arranged.

A Note for the People Who Are Already Worried

I’ve been getting messages for a while now. Nice ones, thoughtful ones. People asking: how do you make this safe? How do you constrain it? Where are the types? Should we sandbox this? Where are the guardrails? What if an object modifies another object in a way you didn’t intend? What if the whole system just... wanders off?

I recognize this. I wrote about it last year, actually. The pendulum. The informalists discover what’s possible, and then the formalists arrive and make it reliable. It’s been happening since Kay and Dijkstra were staring at each other across a philosophical canyon. It’ll happen here too.

But back to the beginning when we were talking about cathedrals. Nobody proved the flying buttress would work before building one. They figured out how stone behaves by spending centuries leaning it against other stone. The formal engineering, the structural analysis, the load calculations, all of that came after. You can’t formalize a thing you haven’t found yet. You don’t even know what the right constraints are until you’ve watched the system do something you didn’t expect.

And prompt objects keep doing things I don’t expect.

So yes. One day, someone will build the type system for this. Someone will write the formal verification layer. Someone will figure out what “correct” means for a system that modifies itself at runtime, and they’ll build tools that enforce it. I look forward to that. I’ll probably use those tools.

But right now we’re still in the part where the stones are learning to lean. We’re still figuring out what shapes are possible. And if you formalize too early, you lock in the wrong shapes, and you end up with a very well-typed pyramid.

I’d rather have an untyped cathedral, for now.

What’s in the Box

Version 0.5.0 just published a little while ago with a few new things.

An ARC-AGI solver template built with prompt_objects. A starting point. Fork it. Rearrange the objects. The system is designed to be reshaped while it runs. Have some fun trying to solve some ARC-AGI problems. If you come up with some fun new ideas, let me know!

# How to get started:

$ prompt_objects env create [YOUR ENVIRONMENT NAME] --template arc-agi-1

$ prompt_objects serve [YOUR ENVIRONMENT NAME] --openAn updated interactive web-based authoring interface so you can build out and test your prompt object systems. There’s a lot baked into it. If you have questions or want a walkthrough come chat in discord.

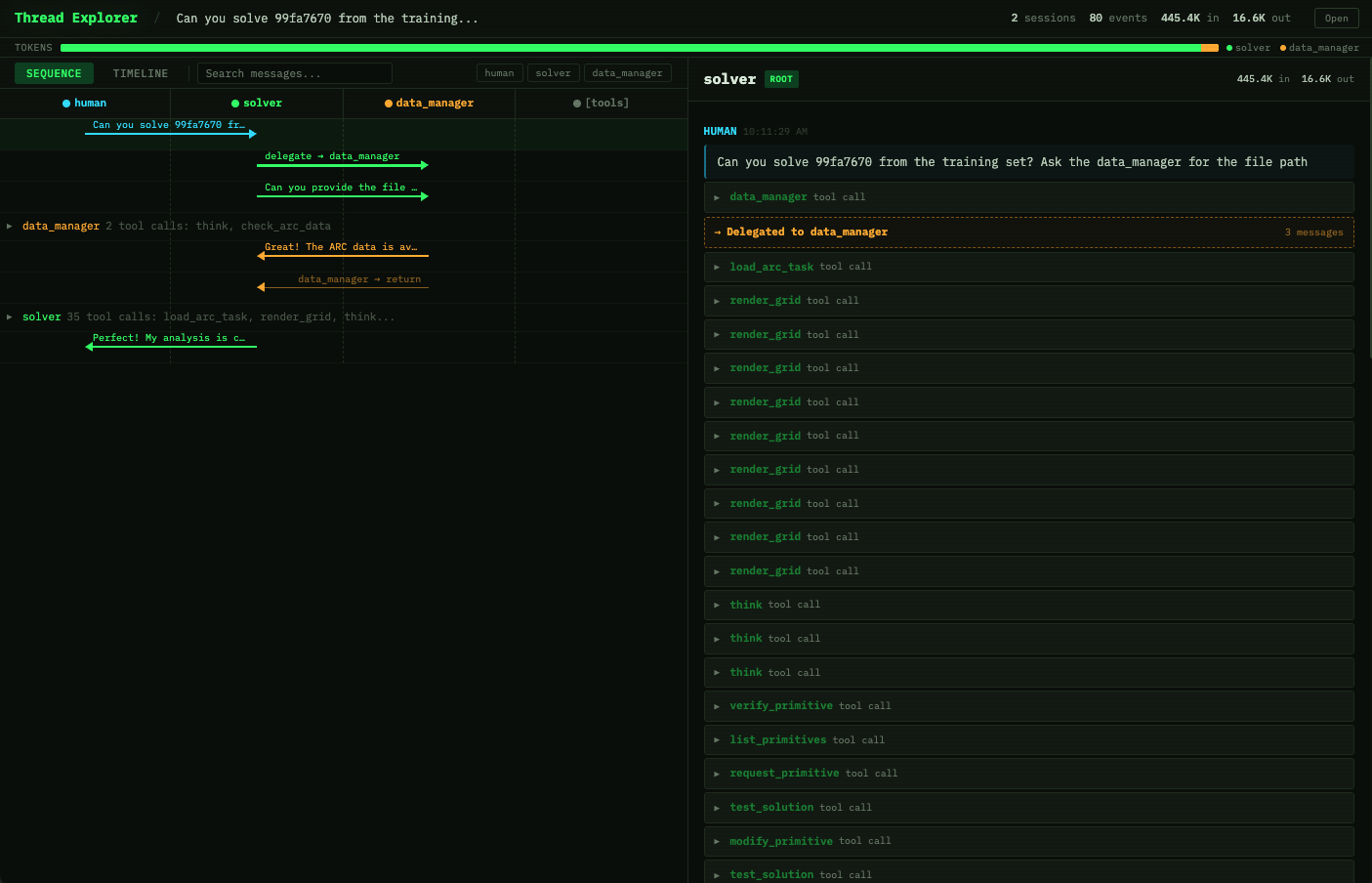

A thread visualizer so you can trace through an exported execution and watch the system think. A conversation. “Object A thought X. Told B. B disagreed. A created C. C found the pattern.”

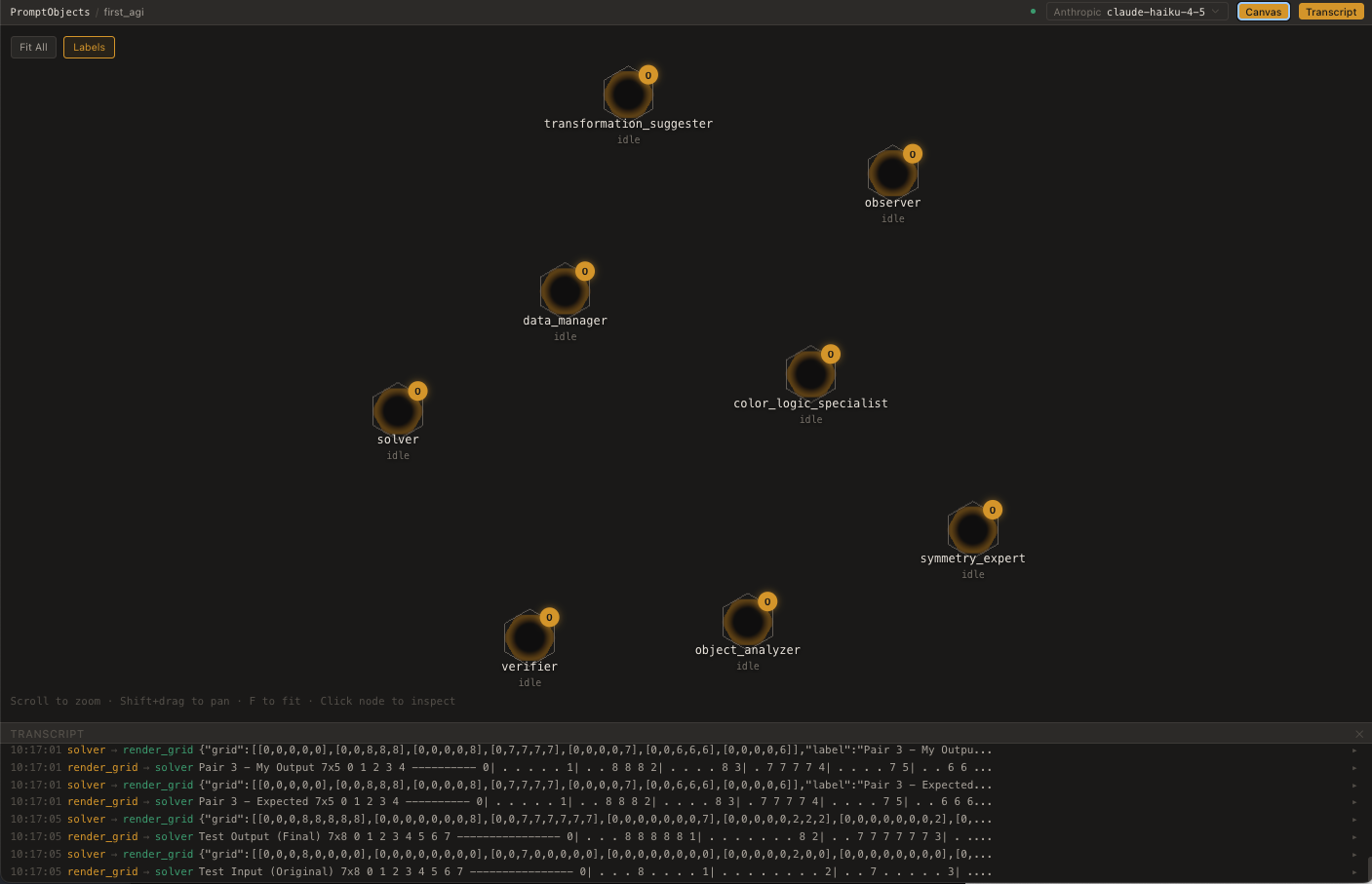

An experimental canvas-based interface for watching your prompt object systems in action. I’m still messing around with this one, but sometimes you want to have a spatial understanding of the communication going on. If you have suggestions for making this better, I’d love to hear them!

Check it out on GitHub or gem install prompt_objects from Rubygems

One More Thing

The ARC Prize team recently announced ARC-AGI-3, and it’s their first “agentic evaluation benchmark.” It tests interactive reasoning: exploration, planning, memory, hypothesis testing, learning across steps.

To me that sounds like the description of what prompt objects do by default. Almost by accident.

Who knows if prompt objects will be good at ARC-AGI-3. But the architecture was built for exactly that kind of problem, because message-passing and interpretation naturally produce those behaviors. I didn’t engineer exploration as a feature. It just showed up because the stones were arranged that way.

Almost all air. Almost all glass.