How Do You Speak Pidgin To A Probability Distribution?

Why We Still Need Frameworks When AI Can Build Everything

Hallucinations - 01

A master carpenter kept worn wooden jigs in his workshop—templates smoothed by ten thousand cuts, guides that knew the exact curve of comfort.

A brilliant apprentice arrived with a programmable machine. "Master, why keep these old blocks? My machine can cut any shape imaginable."

The master handed her rough lumber. "Make me a chair."

She programmed for hours—coordinates, angles, measurements. The chair was perfect. It was correct. It did not sing.

The master placed his dovetail jig against her machine and whispered: "Dovetail. Like this."

The machine understood immediately.

"Your machine can cut anything," said the master. "My jigs remember everything. Which is wiser—the tool that knows all possibilities, or the template that knows which possibility matters?"

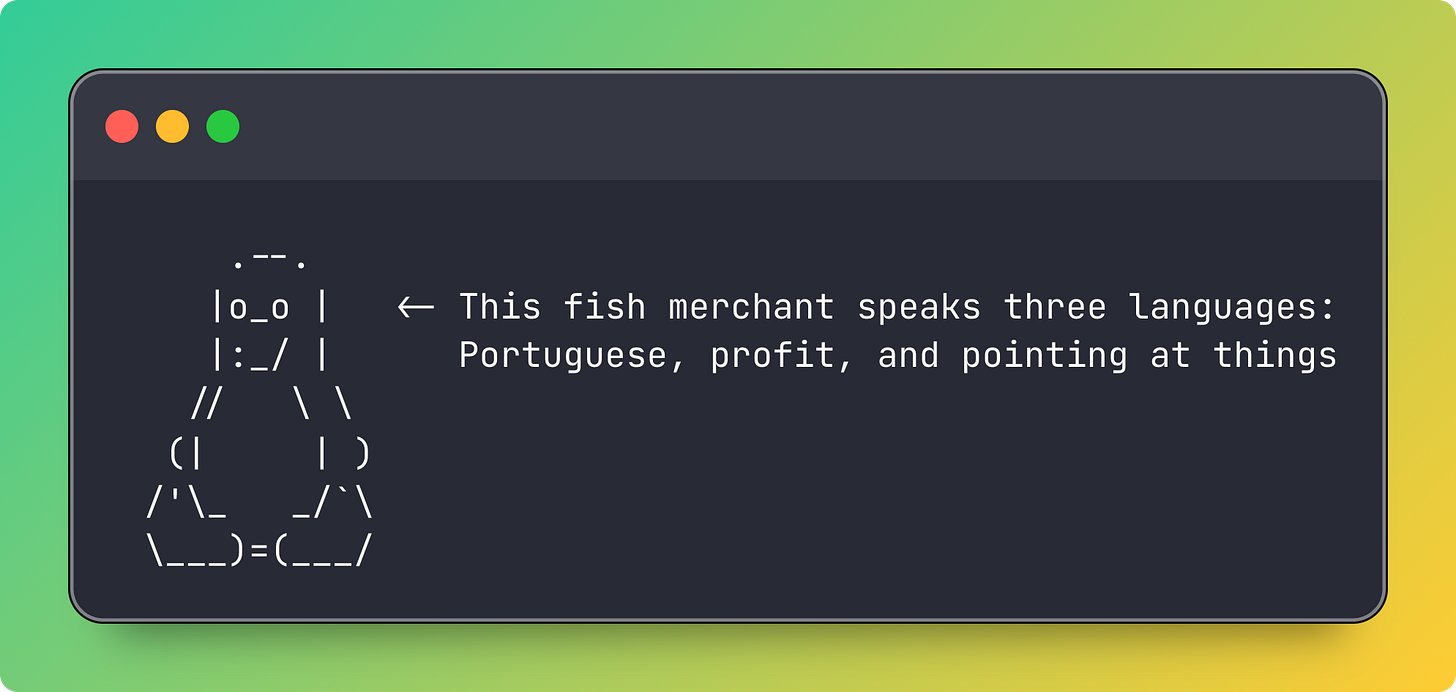

Something happens when people who don’t speak the same language need to trade spices, or fish, or coconuts or whatever. They don’t have time to learn each other’s entire language so they do the only thing they can do.

They invent a new language. Right there. On the spot.

How Humans Have Always Been Hackers

Picture this: It’s the 1600s, and Portuguese traders are trying to do business along the West African coast. It would be a long time before Babelfish.com would come out and solve this problem for them. But what they did have was the universal human superpower: the ability to point at things and make sounds until somebody understands.

"You… give… fish?”

”Me… want… cloth!”

And just like that a pidgin is born. Not broken Portuguese, not broken local languages, but something entirely new. A bridge built from both sides, meeting somewhere in the middle.

Pidgins aren’t anybody’s native language. They belong to everybody and nobody at the same time. They’re pure function, stripped of all the complicated grammar rules that make high school teachers cry. No subjunctive mood. No seventeen different past tenses. Just: “Yesterday me go market.” Everyone understands. The fish get sold. Life continues.

The Plot Twist

Sometimes, just sometimes, children grow up speaking these pidgin languages as their first language. Their first language. Imagine your mother tongue being something your grandparents invented to buy fish.

When that happens, something magical occurs. The pidgin transforms. Like a caterpillar, except instead of becoming a butterfly, it becomes... a real language? A creole. Complete with all the complexity and poetry and irregular verbs that make language class so frustrating.

Hawaiian Pidgin (actually a creole (I know, I know…)), Haitian Creole. Tok Pisin in Papua New Guinea. What started as “just enough words to trade fish” became languages that people write love songs in, tell their children bedtime stories in, dream in.

(See where I’m going with this yet?)

Speaking Creole to Probability Distributions

Fast forward to now. Everyone's talking about how AI agents write code. They build entire applications while you're making coffee. They debug faster than you can say "undefined is not a function."

The immediate question everyone asks: "Why do we need frameworks at all when the machines can just… write whatever we need?"

But I think this is the wrong question. It’s like asking why Portuguese traders needed pidgin when they could have just learned all the local languages perfectly.

What Frameworks Really Are (A Meditation)

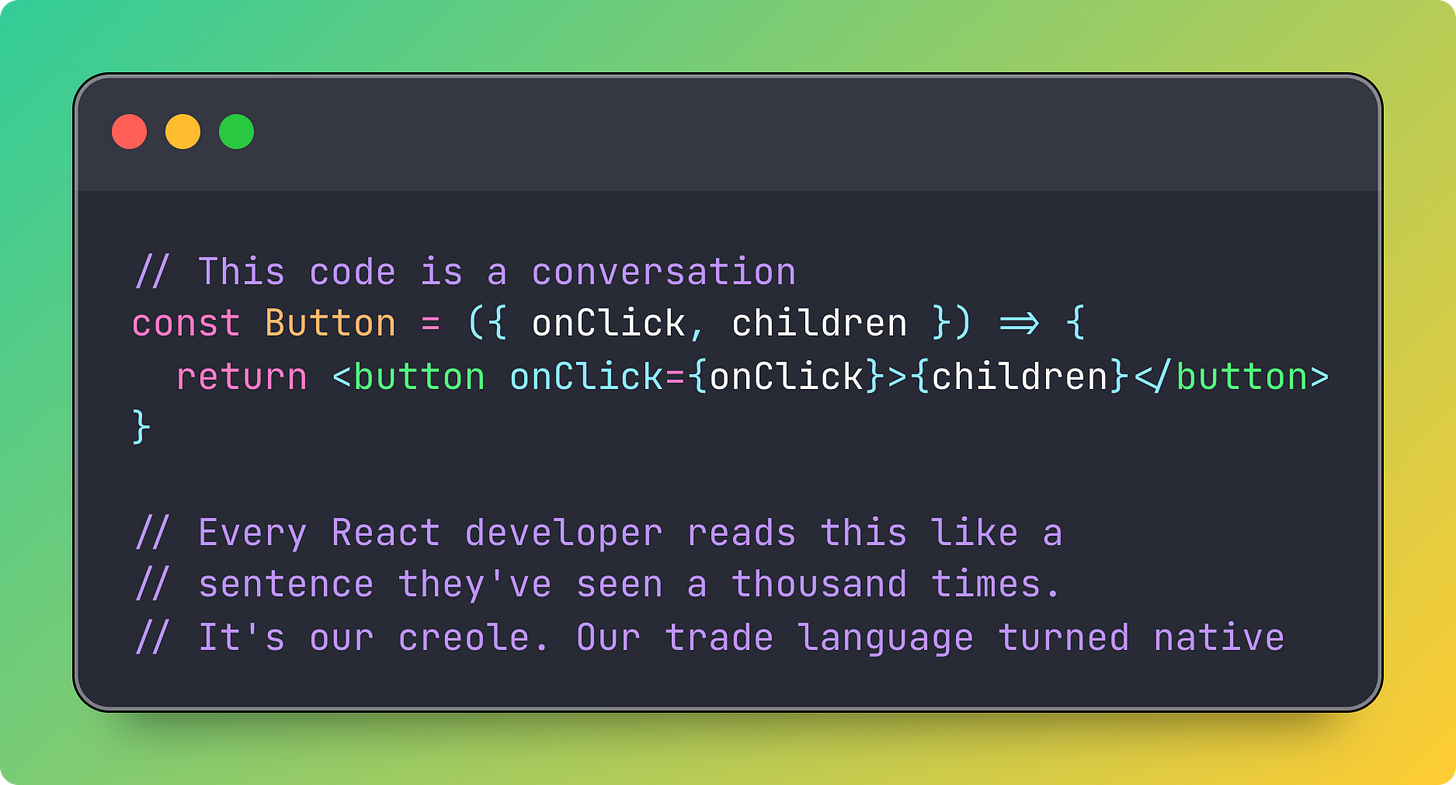

Think about what a framework really is.

No, really think about it. I’ll wait…

It’s more than just a bunch of pre-written code. It’s a shared vocabulary. When I say “component” to another React developer, we both know exactly what I mean. When someone mentions “ActiveRecord,” every rails developer conjures the same mental model and cringes at the same N+1 query memories.

And this is what the “AI will replace frameworks” people are missing: Even when AI can write perfect code in any style, we still need to talk about that code. With humans. With other AIs. With ourselves six months from now when we’ve forgotten everything and are basically different people who hate our past selves.

Imagine trying to describe your application without frameworks:

“I need the thing that responds to HTTP requests and returns JSON, but like, organized in a specific way with middleware and… you know what I mean?”

Versus with frameworks:

“I need an Express server with JWT middleware.”

Done. Everyone knows exactly what you’re talking about. The AI knows what to build. Your team knows what to expect. Your future self knows what they’re looking at and only slightly hates current you.

The Frameworks We Know and the Frameworks We Don’t

Rails is a creole to Claude. React is a creole to GPT-5. They’ve seen so much Rails and React in their training data they’re essentially native speakers.

It’s like watching someone who grew up in Paris order coffee. Effortless. Natural. Slightly condescending to tourists.

But when it’s your company’s internal framework. The one the DevOps engineer built before they left for that farm in Vermont. The one with documentation that’s mostly TODO comments and a README that just says “should be self-explanatory. dm me with any questions” even though they’ve been gone for two years.

This is a pidgin situation. The AI has never seen it. You need to teach it the language while you’re using it. Every. Single. Time.

The Pidgin Conversation Protocol

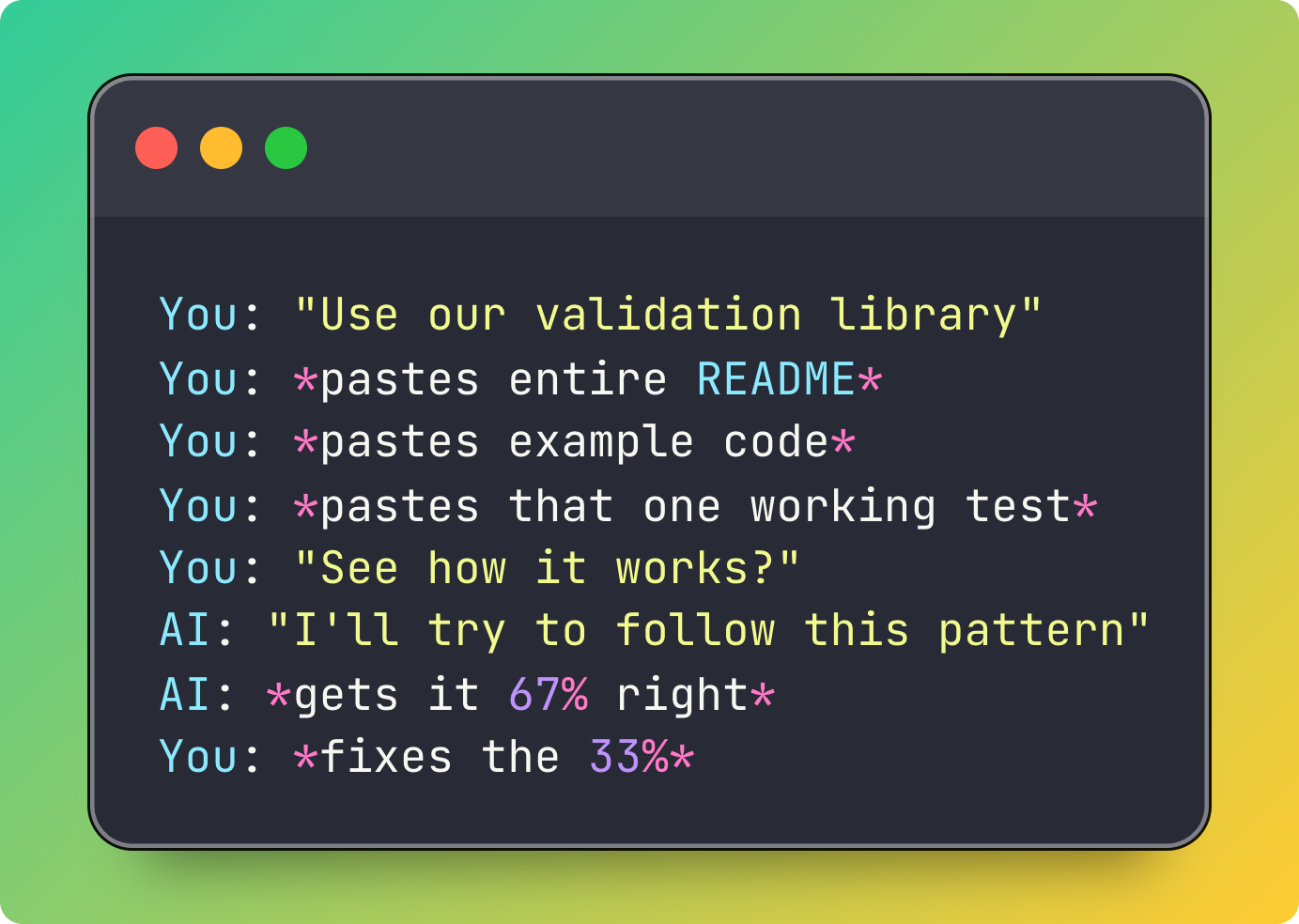

When you’re working with a pidgin framework (read: anything not in the training data), the conversation changes:

And honestly? Sometimes it works. Like those traders in 18th century Canton who managed to build entire commercial empires on “you give tea, me give silver.” Functional, if not elegant.

Enter VSM: Trying To Build Better Frameworks as Pidgins

(I’ll spare you the digression about cybernetics this time…)

I’ve been working on this agent framework called VSM, (stands for Viable System Model). It’s basically me trying to figure out how to build frameworks that make it easy to speak pidgin to AI.

The framework is designed to let you easily create specialized, CLI-based, tool using agents backed by an LLM that you can chat with. We just released version 0.2.0 with a few new features, one in particular is focused on exploring this pidgin problem.

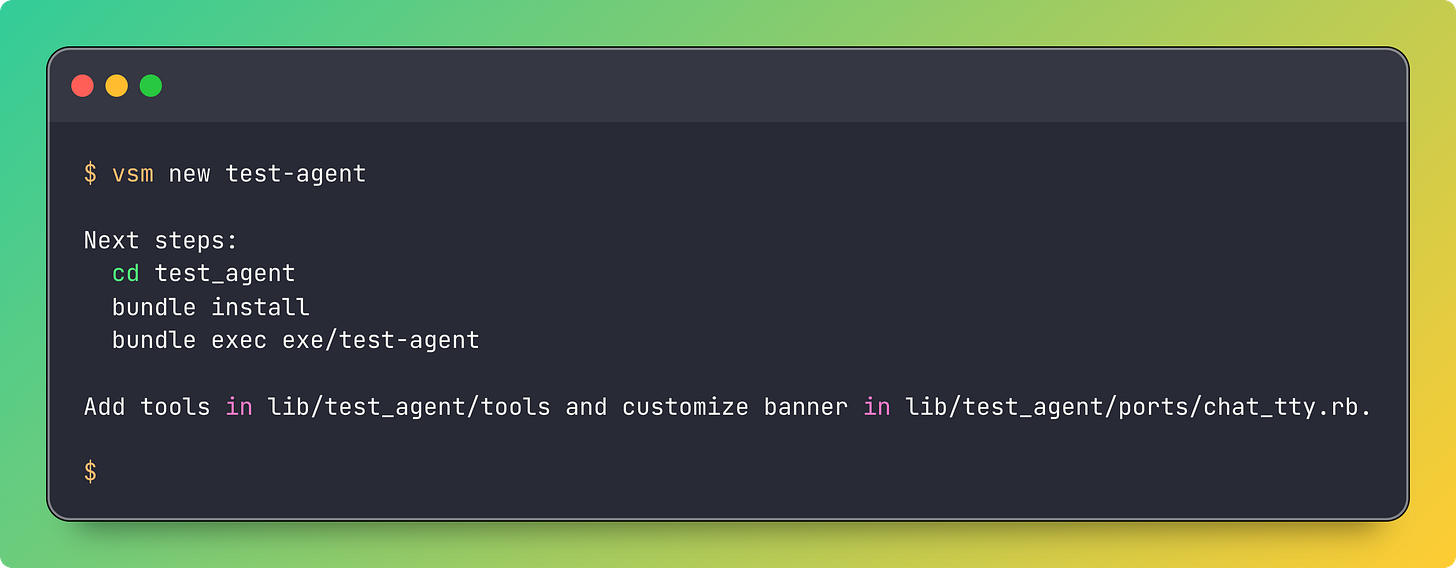

1. The CLI Generator

Every framework needs something like this. Quickly create a new project with all the boilerplate taken care of and the starter files in the right place.

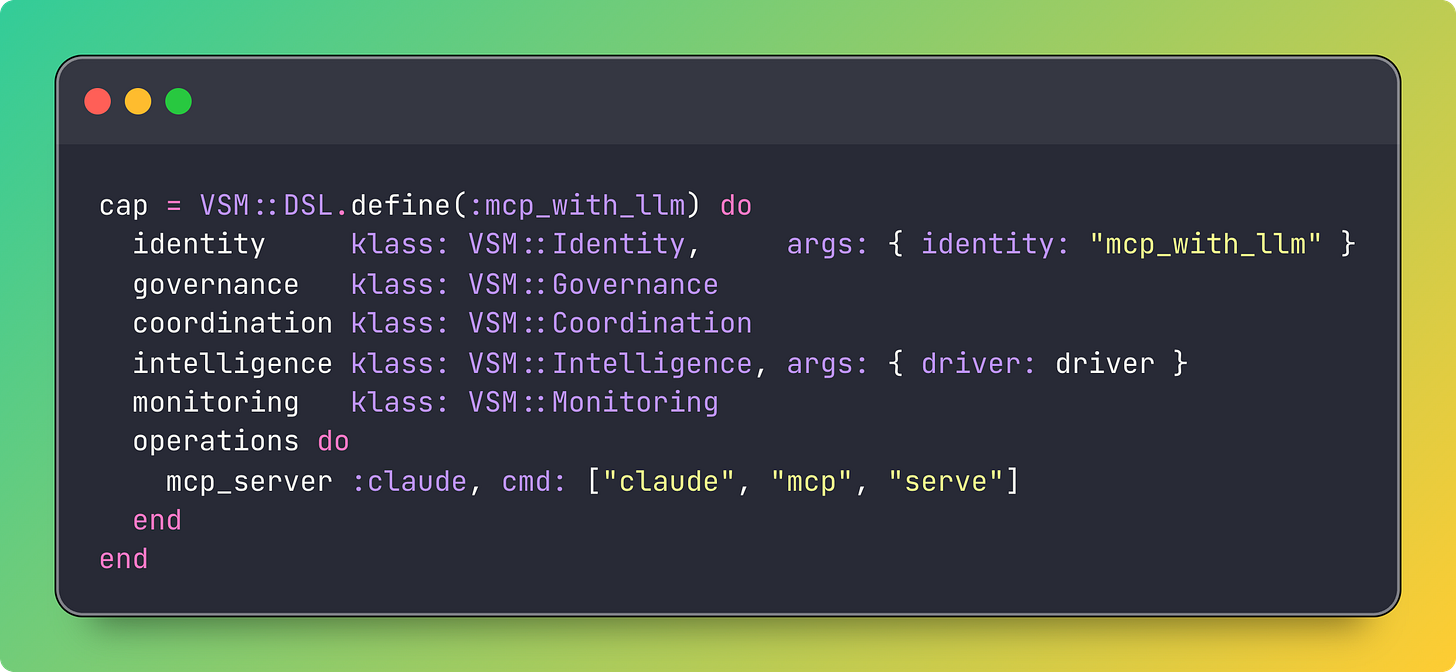

2. MCP Tool Support

Know of an MCP server with tools you already want to use? Drop it in and chat with it immediately.

3. Meta-Tools

This is the fun part.

Ruby lets you ask code about itself:

“What methods do you have?”

“What are your arguments?”

“What is your purpose?”

Take that ability, combine it with some documentation, and suddenly you have an agent that can explain its own operations.

Want to see it in action? There’s an example to play with in the library in examples/10_meta_read_only.rb.

This is all just setting the stage for the next release. Coming up next, we’re going to give these agents the ability to generate their own tools that fit into the framework and then run them, live.

A Small Observation About Expertise

You know who’s getting the most out of AI coding assistants right now? Senior developers. People who already speak Rails or React or whatever fluently.

They’re having full creole conversations. “Add auth with JWT, Postgres backend, refresh token in Redis.” The AI just… does it. Because they’re both native speakers in the same linguistic colony.

But beginners? They get pidgin. They get “make user login thing happen” and a pile of code that might work but probably also sends passwords to console.log because nobody specified not to.

The experts are native speakers talking to native speakers. Everyone else is pointing at coconuts and hoping for understanding.

(There’s probably a deep philosophical point about inequality and access to technology here, but I’m going to leave that for someone with a sociology degree and more coffee than me.)

Where This All Goes

Maybe frameworks don’t become obsolete. Maybe they become… different. Instead of being shared assumptions baked into code, they become active participants in the conversation. Teaching assistants. Translators. Linguistic bridges across the sea of incomprehension.

Maybe frameworks become self-aware. Not like, Skynet self-aware. More like… aware that they need to explain themselves. Conscious of their own patterns. Able to teach their own idioms.

So that’s what this VSM experiment is all about. Can we build frameworks designed for pidgin conversations? That know they’ll be talking to probability distributions who’ve never seen them before? That can teach themselves while being used?

I think maybe yes? But also I’m building it while thinking about it, which is like trying to explain swimming while drowning, except the water is Ruby and the drowning is just regular software development and actually maybe this is another metaphor that got away from me.

In Conclusion

Look… all frameworks are pidgins until they’re not.

Rails was a pidgin once. Someone just used it long enough that it became the way we think. Now our AIs dream in has_many :through associations. They wake up in cold sweats worrying about N+1 queries they’ve never actually experienced.

The frameworks we use shape the thoughts we can think. The pidgins we speak become the creoles our children inherit. The patterns we establish today become the native languages of tomorrow’s machines.

What will they dream in tomorrow?

I realized I never actually answered the question in the title. How DO you speak pidgin to a probability distribution? Very carefully, and with lots of examples, and maybe some ASCII art for emphasis. But mostly? You just keep talking until something clicks.

Or until the context window fills up. Whichever comes first.

I’ve noticed you build most of your projects on Ruby/Rails. I’m curious what drives that choice. Is it mostly about speed of development, the ecosystem, or something else? I’d love to understand your reasoning since you’ve clearly got a lot more experience with it.